- Home

- Nura Maznavi

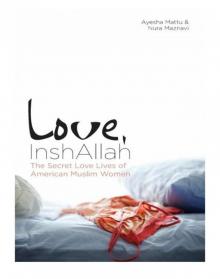

Love, InshAllah Page 17

Love, InshAllah Read online

Page 17

Toward the end of the evening, my father suggested I make some tea and then beckoned Luca over.

“Why don’t we sit outside in the garden?” he asked. Luca’s eyes widened, and he glanced at me. I nodded reassuringly. He followed my father out to the patio, and I watched them sit down on my father’s large swing.

“Okay, Papa, I’ll make tea for you guys,” I called out. I filled the kettle with water and then looked over at my brother. “Shit, what do you think? You think it’s okay for me to leave him alone with Dad?”

“Yeah, don’t worry, Leila. Dad’s harmless,” my brother said.

Once the tea was ready, I placed the saucer and cups on a tray with a few almond biscuits and walked outside. When he heard the clinking tray, my father looked up and smiled at me. “There she is,” he said jovially. “I need my tea every night. It’s my drink.” He winked at Luca. “You know, we Muslims don’t drink alcohol, but tea is like my alcohol.” He reached for the cup and took a noisy slurp. “Ahh, very tasty, Leila. Even though she doesn’t live at home anymore, she remembers how to make her father’s tea, right, beta?”

I smiled. “Of course, Papa.”

“Come sit, beta.” He patted the empty space on his other side. The three of us sipped tea, rocking slightly back and forth on the swing as the crickets chirped and the scent from my father’s jasmine plant enveloped us.

When I dropped Luca off at his hotel that night, he asked, “So, am I going to get to meet your mother?”

I sighed. Other than my mother’s absence, the evening had passed smoothly. “I don’t know, Luca. Does it matter?”

“Of course it matters. She’s your mother,” he responded. I tried not to get upset at his answer. He knew about the long periods of estrangement in my relationship with my mother. Even when we were on speaking terms, our conversations throbbed with unspoken resentments, disappointments, and anger. She factored so little into my daily life, why did it matter that Luca had not met her?

“Look, Luca, you have met the important people in my life. You know that my mother and I don’t get along, and that she decided not to come tonight.” I uncurled my fists and shook my hands out. You know why she wasn’t there. Don’t make me say it. “But look at all the food she made for you,” I offered placatingly.

“I want to see you happy in your family, Leila. That’s all,” he said gently.

“Well.” I put my arms around his neck and smiled at him. “I’m hoping to have my own family soon.” I paused and lowered my eyes. “With you, and I’m sure I’ll be very happy there.”

With three weeks left until my move, Luca flew to New York for one last visit. Even after three years, I still got butterflies in my stomach before our reunions.

When I look back now, I wonder how the conversation started. Each time, it hurts to remember.

We had just come back from dinner with friends in the West Village. Luca was sitting with his legs resting on a box. I was at the kitchen sink, rinsing mugs for tea. We were talking about our life in Luxembourg and having children.

“Well, Italy should definitely be our home base,” Luca said.

“What do you mean?” I asked from the kitchen, over the sound of running water.

“My parents are there, and Italy’s my home. It should be our home base.”

“But it’s not my home, and I don’t speak the language.” I laughed. “Why don’t we choose another place for our home base?” I came into the living room, wiping my hands on a striped dishcloth.

“Like where?”

“Like, I don’t know, but something we decide together. Maybe London?You like London, and I lived there as a kid. I have family there,” I offered.

“Family that you never visit when we go there?” he asked with a snort. He was right. I didn’t particularly like my banker-wanker cousins in London, and dreaded seeing them.

“I don’t know, but I know that we should agree on something together. Italy’s not right for me. I feel so foreign there.”

“But our kids need a stable home. Italy would be good for them,” he insisted.

“Hey, I lived in five different countries growing up. I never had a ‘home base,’ and I’m perfectly fine,” I replied.

“I don’t know—you seem so unstable most of the time, never feeling comfortable anywhere, running from one country to the next,” he said, looking me straight in the eye.

“You think I’m ‘unstable’?” I repeated slowly.

“I mean, confused. You’re always confused about where you belong. I don’t want my kids to have the same upbringing as you did.”

“Your kids? What are you talking about? What’s wrong with my upbringing?” I trembled.

“Well, your religion. It’s so strict and severe. We can’t raise our children Muslim,” he said firmly.

What was going on? How had this never come up before? I had not planned on raising our children Muslim, but I wanted them to be exposed to all aspects of their heritage, including Islam.Yet the way Luca spoke, it was as if he wanted our children to have nothing to do with my religion. Part of me felt betrayed; I had spoken with him honestly about my upbringing, in order to share why I was so opposed to a strict religious life.

“What do you mean, we can’t raise our children Muslim? What are you trying to say?”

“I’m trying to say that our children should be raised with one culture and one religion so they aren’t so confused. They should be raised Italian Catholic.”

“Wait a minute, how can you say that? They are going to be my children, too! And you want them to be something so foreign to me? Italian, Catholic—this is not me. I’d feel so distant from my children.”

“So, how do you want to raise them?” he asked, his lips tightening.

“I guess with both our cultures, both our religions. Or how about just secular? No religion,” I stammered.

“No religion? Our kids need to have morals and values. We can’t raise them with no religion,” he replied angrily.

“Well, then, let’s raise them with both religions. We can teach them about Catholicism and Islam,” I said, giving him a small, conciliatory smile.

“Okay, and how do you see that working?” He folded his arms across his chest and sighed impatiently.

“We could celebrate Christmas and Eid. We could take them to church and to the mosque.”

“The mosque? You want to take our kids to the mosque in Milan? Where all the terrorists hang out?”

I sat in stunned silence. “Where all the terrorists hang out,” I repeated slowly, shaking my head. We looked silently at each other for several long minutes. “What’s happened to you, Luca? You sound like your fascist leader Berlusconi.”

“We need to think carefully about these things, Leila.”

“I don’t understand what’s going on with you, Luca. The whole world out there is saying awful things about Muslims, and now the person with whom I will share a home, have a family, is saying the same things. You should know better. I should feel safe with you, understood by you, but instead you’re saying crazy things about my religion and my upbringing, telling me I’m unstable, confused.” My voice cracked. “I don’t understand.” I fell into a chair because I could no longer stand. I covered my face with my hands, trying to steady my breath and body.

He stood up and came over to me. He knelt down and tried to move my hands from my face. “Look, amore, I need to be able to speak honestly with you. I want my kids raised Italian and Catholic. They need that structure and stability. I don’t want them growing up Muslim in Italy or London or anywhere else in Europe. They won’t fit in and will have a lot of difficulty in life. Eh, amore,” he said softly, “please look at me.”

I sat there with my face covered for a long while. Who are you? Have you always been like this and I just never noticed? I waited for the shaking in my hands and my legs to subside, for the hot white rage churning in my stomach to slow down, for the tears spilling through my fingers to stop. When he tried to tou

ch me, I shook him off, keeping my palms glued to my face, my fingers locked together in front of my eyes. How can you feel this way about Muslims and say you love me? Finally, I took a deep breath, placed my hands on my knees, and looked up.

“Get out of here,” I said quietly, staring straight ahead.

He stood up, gathered his belongings, zipped up his bag, and left.

When I heard the door close, I lay down on the floor with my eyes shut and my hands by my sides. I felt so terribly afraid about what had just happened. It felt irreversible. Still, I waited for him to come back, hoping that it had been a moment of hubris and that we would be fine, that our life together in Luxembourg still awaited us.

I never saw Luca again.

So I Married a Farangi

Nour Gamal

My entire life reads like a transatlantic tennis match—Egypt–America; Bahrain–America; Kuwait–America; Egypt–Ireland; Egypt–England. When I was a child, my family moved between the Middle East and America whenever my parents relocated for work. As an adult who felt as if she belonged everywhere and nowhere, I kept moving because it was the only real mode of life I’d ever known. As a result, the most difficult question anyone could ever ask me was “So, where are you from?”

Despite this deep-seated identity crisis, there was one thing I was always sure of: I would grow up to marry a nice Muslim boy of (any) Arab origin and make my parents happy.

The signs that I was a Farangiphile appeared at a very young age, but I ignored them—just as I chose to spend my first year at university as an engineering student, despite the signs that I belonged in the humanities.

It began with Neil Fields in the second grade at the international school I attended in Bahrain. Neil was a wild one and, in retrospect, most certainly had ADHD. But dear lord, did I love him. He was always trying to emulate Chuck Norris by climbing up the walls or throwing paint around or knocking a desk over. What was there for a chubby tomboy like me not to love? Alas, it was not meant to be, as he only had eyes for Dutch Barbara and her stupid stick-straight, honey-blond hair. Also, we were seven.

We moved back to New Jersey in 1988. Fourth grade brought Jonny, who set the tone for all future Farangi crushes. Jonny and I were the best of friends. He was like my white, Coke bottle lens–spectacled, silky-straight-haired brother from another mother. He was also the first in a long line of boys I would insist were “just friends—no, really,” but about whom I had some very unfriendlike feelings. This was my coping mechanism.

My parents are observant Muslims who would take us to the mosque in central Jersey every Sunday for religion and Arabic classes. Starting when I was very young, they drilled into me that dating is haram and that interactions with the opposite sex are to be undertaken with that in mind. But they were pretty accepting of my having boys as good friends. I came to understand that my interactions with boys (and, later, young men) would not be criticized as long as they took place within the context of friendship. And boys didn’t really find me attractive as more than a friend until I was sixteen, anyway. Though I had many crushes, I only ever behaved towards them in a manner that could be explained away as something one friend would do for another friend. If I gave a crush a Valentine’s card, he would get the same one that all my other friends got. If I gave him a mix tape–that early 1990s symbol of devotion—I would be sure to qualify the gift by claiming that I’d made the tape for myself and just thought he might like to check out the songs. If one of my girlfriends happened to ask me if I thought my secret crush (they were always secret, as I was never outwardly boycrazy) was cute, I’d respond nonchalantly, “Oh, him? Um, I guess he’s alright. We’re just such good friends that I can’t think of him that way.”

During the entire fourth grade, Jonny and I sat next to each other on the bus to and from our private elementary school in New Jersey, and generally did everything together. We partnered in class and spent most of our time at recess together, and he was the first guest on my birthday party invite list. The only time there was any indication of something “more” between us was when our bus would pass Lovers’ Lane and we’d both momentarily jump to different seats because, ew, cooties.

Jonny was followed by a string of blond-haired, blue-eyed biker/skater boys: Griffin, with his scientist parents who wouldn’t allow him to eat tuna because of the dolphins; Ivan, who had the raddest skater-boy haircut and whose parents were Eastern European exiles; Brian, the seemingly all-American son of an abusive alcoholic; Seamus, the son of a recovering alcoholic, who had been sexually abused as a youngster.

Did I mention my penchant is not just for white boys, but for tragically damaged white boys? After all, what better excuse is there to be close to a guy “only as friends, Mama and Baba” than to claim you’re spending so much time on the phone and after school with him because you’re helping him out?

The list goes on. Despite spending my middle- and high-school years in post–Desert Storm Kuwait, I somehow managed to limit the scope of my crushes to the troubled-white-boy contingent, with almost no exceptions. In fact, until I started college, there were only two blips on my white-boy-loving radar—most memorably, Mohammed.

Mohammed was, if we’re to be honest, much more than a blip. He was my first love. Our relationship was kindled over his ability to use this newfangled thing called the Internet to find Kurt Cobain’s suicide note, which he read to me over the phone that first heady summer of ’96. From that point on, we began writing each other passionate love letters (one of which he even wrote in his own blood to convey the depth of his affection).

I was sixteen going on seventeen, and this was real love, man—whether or not I admitted it to myself at the time.

But despite his name (and actually, most people knew him by his decidedly non-Arabic nickname, Freddie) and his chocolaty-brown complexion, Mohammed’s soul was white as the driven snow. He played lead guitar in a band. He wore his hair long and lived in plaid flannel shirts. He wanted to be a rock star (alongside being a dentist, of course) and live the life when he went off to college in Canada later that year. My point is, Freddie was as Farangi as you could get without actually being a Farangi.

My relationship with Mohammed/Freddie ended—as so many tragic first-love stories seem to—when my parents found one of the notes he’d written me. This commenced a three-month period of hand wringing, head shaking, and fierce under-the-breath yelling (is this a particular specialty of Arab parents?) about how ashamed they were that I was carrying on in this manner with someone whose parents they were friends with. They then grounded me for two months and told me to never speak to him again. Despite the fact that I had to see Mohammed every day in school, I dutifully did as I was told. I refused to be sad or sorry about the breakup, and resolved to forget about it. I would not let something as silly as love or affection conquer me or compromise my relationship with my parents or my faith.

My mother often lamented that her children’s upbringing in a generally Western, non-Islamic environment meant that many of Islam’s teachings were lost on us. But they certainly instilled in me the idea that Allah is all-knowing and parents are His eyes on Earth. My first year in college on the East Coast of the United States, with my parents still in Kuwait, I would be back in my dorm room every night for the 10:00 PM curfew my parents had “suggested” to me before I left for college. I was always sure that somehow they would know if I wasn’t home at the allotted time.

It was only after I’d been in college for three years that I started to recognize realities I had denied about myself—namely, my long history of white-boy loving. I set out on a mission to deprogram myself. I wouldn’t ever end up with a white guy—because my mother had made clear to me in no uncertain terms that she would not accept my rewarding her leniency in allowing me to live in the United States alone with bringing home a perfectly nice, intelligent, and decent non-Muslim man. So I focused on getting clean.

Of course, I did this by becoming entangled with the smartest, kindest, most hel

pful—and whitest—Jersey boy ever. I followed that with a relationship with the most devastatingly intelligent, musically talented Midwestern white boy ever. Followed by . . . well, you get the idea.

But I persevered, and after six years in the States, I packed up my things and hauled ass back to Egypt—where my parents were now living—giving myself one last-ditch chance to kick the whitey habit.

But Allah has a wicked sense of humor, y’all.

I met Gabriel in May 2004, just six months after I moved to Cairo. Our first meeting, through my best friend, was unremarkable. Gabriel had just arrived from England to finish up his research for his master’s degree dissertation on governance in Egypt. His uncle was my best friend’s master’s thesis advisor, and had asked her to show Gabriel around as a favor to him. He seemed like a lovely guy—which explains my lack of immediate attraction to him. (Remember, I like ’em damaged.) So we became friends—really just friends.

Then one day a few years into our comfortable, close friendship, I started to think that maybe there could be something more between us—a thought that I promptly shut down when Gabriel started seeing an acquaintance of mine. Sloppy seconds were not my style.

But a few weeks later, they called it quits and I became Gabriel’s go-to girl. We started hanging out like never before, and he began calling me late at night to check that I had arrived home safely from whatever outing I had been on. It was during this time that he told me, “If you were my type, you’d have to get a restraining order to keep me away from you, because we get along so well otherwise.” Just the sort of lukewarm praise every girl wants to hear. I was finally at peace in my relationship with my parents, with Islam, and with my heritage. I didn’t want to risk shaking that up by taking a chance on a Greek Brit, even though he had surprisingly nice teeth for a Brit and a wickedly wry sense of humor.

Love, InshAllah

Love, InshAllah