- Home

- Nura Maznavi

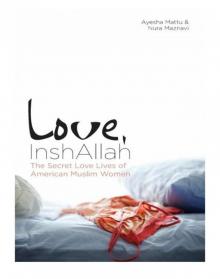

Love, InshAllah Page 16

Love, InshAllah Read online

Page 16

“Oh, amore, me too.” I took his hand. “We’ll make it work.”

The day Luca left, I accompanied him to the train station. We hugged and kissed even after the conductor blew his whistle, signaling the train’s departure. I stood waving until the train became only a small black spot. As I walked back to my studio, the city felt bleak, despite all the Christmas lights, tinsel, and VIN CHAUD signs. I just had to survive one week until I would see him again.

Before I had come to Strasbourg, I had accepted an offer with a law firm in New York. The firm had encouraged me to complete my fellowship and had agreed to hold my position until I returned. As my year in Strasbourg came to an end, Luca and I brainstormed about how we could live in the same city. He had started working for a nongovernmental organization in Milan that focused on development projects in Africa, and was thinking of ways he could work in the United States for this NGO. We briefly considered my moving to Milan instead of New York, but that plan was replete with logistical hurdles, namely, my inability to speak Italian and my significant student loans.

“Luca, I owe over one hundred thousand dollars in student loans; I have to work at a firm for a few years,” I explained to him.

“A few years? What do you mean? You’ll be in New York for at least a few years?”

“Well, I have to repay some of it. I feel so stressed when I think about how much I owe.”

“But what about us?” he implored.

“Well, didn’t you want to study law in the U.S.? Maybe you could apply for a law degree at a university here,” I suggested.

“Yes, it’s true. Every lawyer at the UN had degrees from the U.S.” That summer, as I transitioned from the idyllic life of a researcher in Strasbourg to the demands of a junior associate at a Manhattan law firm, Luca came to New York and stayed with me for two months, working on translation projects for the Italian NGO and researching law programs.

He left one week before 9/11. When the city was attacked, the phone lines went dead and I couldn’t call anyone—not my family in California, not Luca, no one. I felt terrified and alone as I walked from my office in midtown Manhattan to my apartment on the Upper East Side. I couldn’t bear to watch the images playing on the television, so I lay on my sofa, staring into space. It finally occurred to me to send emails, and that was how my family and Luca learned that I was fine. Luca wrote back immediately, insisting on taking the next possible flight to New York, but I told him not to worry and that I still planned on coming to Milan for a holiday in a few weeks.

Luca spent several months working on his law school applications. But because of the economic crisis that followed the 9/11 attacks, graduate programs received record numbers of applications, and Luca was not accepted anywhere.

“Why did I put myself through this? It was for you. I just wanted to be near you,” he said bitterly. My heart ached as I watched him suffer through the disappointment. I wanted to tell him that I was disappointed, too, that I was working hard to repay my student loans not just for myself, but for us, so that we could have greater freedom soon.

With so few employment prospects in New York for an Italian lawyer after 9/11, Luca and I settled into a holding pattern of sorts. We scrimped and we saved, and we used every vacation day possible to meet each other in New York or in Europe nearly every month.

On several occasions, we broke up. He accused me of being selfish and too focused on my career. I cried that he didn’t understand how debilitating my loans were and that, despite my Italian lessons, I could not speak well enough to work as a lawyer in Italy. We always reached an impasse when I insisted on wanting to work.

“But I can take care of us.You won’t need to work,” he assured me.

“What do you mean? I’ve studied so hard to be a lawyer, borrowed all this money for my education. I want to work as a lawyer,” I responded testily. “Your mother is a well-known attorney; your sister is a professor at a big university—why should I be the housewife?”

By this point in the conversation, I knew Luca would pull his trump card.

“You still haven’t told them about me,” he accused softly. There it was—the blow that reduced me to a heap of shame and guilt.

“Luca, I just need to find the right time,” I whispered.

“Amore, it has been nearly two years. You’ve spent the holidays with my family. You stay with my family when you visit. They all ask about you. When do I get to meet your parents? Your sister and brother?”

“Babe, my brother and sister know about you. But with my sister getting married, I just can’t tell my parents right now.” I felt frantic as I thought about my sister’s “perfect” situation. She had met her fiancé at her local mosque’s youth group. He was Pakistani, a practicing Muslim, and fluent in Urdu. Check, check, and check. And he was an engineer. Yet another check. My Pakistani, Muslim, Urdu-speaking parents were thrilled. The only wrinkle was me, the unmarried older sister. My parents initially contemplated holding off on my sister’s wedding until someone could be found for me, but, given my track record of refusing suitors, they decided to move forward with her wedding.

“You know I’d like to go to the wedding with you,” he said. My stomach sank. My parents were devout, practicing Muslims. My entire extended family was. How could I show up with my Italian, Catholic boyfriend to a wedding full of Pakistanis and religious ritual? How would he react to the significant number of women who wore head scarves and the few who were covered in the chador? How would they respond to him? Luca’s appearance at this wedding would be uncomfortable for everyone.

“Luca, I would love to share this wedding with you, but you don’t understand how strict my relatives are. It would be culture shock for everyone. I promise I’ll send you photos and I’ll call you every day, but my sister’s wedding is not the time to introduce you to my family. I’m really, really sorry.”

A long, tense silence ensued. “Why, why are we doing this? How did I end up in this situation?” he wondered aloud.

These conversations haunted me. How had we ended up in this situation? Why was I still so afraid of acting on my commitment to him? When would I be ready to tell my parents about him? My reluctance revealed depressing truths about how I felt about our relationship. But each time I thought about letting him go, sparkling memories surfaced: the two of us whizzing around Milan on the back of Luca’s Vespa, sharing a thick hot chocolate in wintry Paris, holding hands as we walked around the shimmering reservoir in Central Park. I was in love with him, but the consequences were paralyzing.

In the months after my sister’s wedding, my family’s efforts to marry me off intensified. I couldn’t come up with excuses fast enough. Even after a decade of pushing back against my parents’ attempts to arrange my marriage, I still felt pangs of guilt for not doing what they wanted, and they still hadn’t given up hope. My parents expected me to marry a Muslim man, preferably Pakistani. That’s what good Muslim girls did, right? Sometimes their disappointment and frustration were so severe that my mother would threaten to disown me and wouldn’t speak to me for months.

I tried to placate them, sharing with them whenever I met a promising Muslim man—Nabil, the Algerian-French lawyer I met in Sarajevo, or Karim, the half-Tunisian, half-British man I dated when I was studying Arabic in Tunisia—but I knew they wanted to participate in the selection process, and they wanted someone more culturally familiar. So telling them that I had a boyfriend who was neither Muslim nor Pakistani likely meant losing them. Each time I worked up the courage to tell them, Luca and I would have a fight and I would retreat. Was he worth devastating my parents?

My hands felt clammy as I dialed my father’s home office. We exchanged pleasantries, and then my throat went dry.

“Papa, I have to ask you something.”

“Yes, beta, anything,” my father said cheerfully. I took a deep breath.

“What if you had met someone before Mummy, when you were studying in St. Louis? What if she was gori and not Muslim?” I heard si

lence on the other end. He cleared his throat a few times. I imagined him holding the receiver and looking out at his beloved plants on the patio.

“Well, I don’t know. I never met anyone.”

“But what if you had?” I insisted.

“Well, let’s see . . . I guess if I loved her, then that’s all that matters.” My father’s heartfelt response surprised me.

“What if I met someone I loved?”

“Well . . . ” He coughed and then was quiet. “Uh, well, then, that’s all that matters.” I looked into the phone, astonished.

“Really, Papa? Really?” I paused. Come on, just tell him. “Because I have.”

“I see. When did this happen?” he asked gently.

“Two years ago.”

“Oh, beta, two years? It must be serious.”

“Yes, it is, Papa. It is.” I nodded vigorously into the phone.

“So, what’s his name?”

“Luca. He’s Italian. He lives in Milan.”

“Milan—what a beautiful city. I went there once for work.” We both sat quietly on the phone. Finally, he asked, “Do you think he’ll convert?”

“I’ve never asked him.”

“Well, you know our religion does not accept a woman marrying a man outside Islam.”

“It doesn’t make sense why a Muslim man can, but a woman can’t.”

“It’s because a woman is more likely to convert for her husband than a man for his wife,” he returned evenly.

“But I don’t feel like religion is a big part of my life, so why have him convert?”

“Because it’s a big part of your family, and he won’t fit in if he’s not Muslim.”

“Shit, Dad, I barely fit in with all our fundo cousins and relatives.” I sighed.

“Watch the language, beta.You’ll fit in even less with a husband who is not Muslim.” I exhaled loudly.

“Just ask him, beta. Do that for me.”

Even though my relationship with my faith had shifted after 9/11, I still couldn’t bring myself to ask Luca to convert. Following the attacks, Muslims in America were vilified. Under increasing scrutiny, and whether willingly or not, we each became an ambassador of our faith. In the face of tremendous fearmongering, I found myself describing the virtues of Islam, its inherent peacefulness, and its similarity to Judaism and Christianity to my friends, my coworkers, and even the West Indian lady at the organic market down the block.

But even though I talked about Islam more openly and often, I didn’t practice my faith. I had largely shed those rituals when I had left home for university, a decade earlier. Some habits remained: refusing to eat pork or bacon, greeting a Muslim with “salaam,” and attending Eid prayer once a year. There were moments when I collapsed into the familiarity of prayer, the only spiritual language I knew to access serenity. But, on the whole, Islam’s daily practice did not return.

Luca and I often discussed the shifting political landscape after 9/11, the senseless war in Iraq, and the crazy things happening to Muslims in America. We talked generally about the misperception of Muslims in the world, but I never probed him about his feelings about Islam or how he felt about my being Muslim. I just assumed that he accepted me for who I was.

My mother didn’t believe that Luca and I would work. When I finally told her about our relationship and how he would like to meet her, she snapped, “How do you see this working out? You’re Muslim, Leila. Pakistani. It’s in your blood, your name, your family. He’s Italian. Catholic. This will never work unless one of you converts. I don’t care how much he loves you—marriage takes more than love to work.” She was adamant. “I’ll meet him—if he converts.”

“Ma, I don’t feel comfortable asking someone to convert. I would never convert.”

“But for the sake of the children, the same religion is important. Listen to me, Leila.You’re almost thirty years old.You’ve got to get serious and settle down. Enough with all this nonsense. Enough.”

“Ma, please, just meet him. He’s a really good man—smart, hardworking, and very loving.”

“Leila, I told you, I’ll meet him if he converts. Otherwise, it’s a waste of time. I will not accept a son-in-law who is not Muslim. Is that clear?”

I was typing up a memo to a client when Luca called. He spoke excitedly, telling me that he had just been offered a position as a lawyer for the European Union in Luxembourg. He described the job, the salary, and all the benefits.

“I think now is the time, amore. Come live with me. We can have a really good life in Luxembourg.”

“Luxembourg?” I grinned into the phone. I knew that I had more employment options there than in Milan. “Luca, I’ve never been to Luxembourg, but I believe you.”

I visited him there, and we strolled along the canal, shopped at the local farmers’ market for cheeses, eggs, and fruit, and enjoyed meals at restaurants with mossy stone walls. We also hammered out the details of my move, including all the ways in which I could freelance. I was feeling more financially stable with some savings in the bank, a chunk of my student loans repaid, and no credit card debt. Yes, Luca was right: The time had come.

We also decided that Luca should meet my parents in California before I moved. I told him that they now knew about him, and that this would be my first time introducing a boyfriend to them. His eyes glistened as I spoke. I didn’t mention his converting or my mother’s possible absence from the gathering.

At the end of my visit to Luxembourg, when I boarded my flight to New York, I looked around and imagined my return a few months later. This was going to be my new home. As I stared out the window at the bucolic landscape, I felt relieved. Finally, Luca and I could be together.

I stood anxiously in the arrival hall of San Francisco International Airport. When I saw Luca walk through the gate, I beamed and let out a small squeal.

“Amore!” I waved excitedly and rushed to him. “Welcome to California!” I hugged and kissed him and then wrapped my arm around him. “How was your flight? Are you tired? T’as faim?”

We drove down to Southern California the next day with my brother, a student at Berkeley. When we reached Orange County, where my parents lived, we dropped Luca off at his hotel so he could freshen up and change. My parents were not ready to have my white boyfriend stay under their roof. When I first told Luca I had booked a hotel room for him, he was slightly taken aback. “Oh, a hotel? And where will you stay?”

“Uh, at my parents’ place,” I stammered. “Luca, come on—this is not easy for them. I can’t expect them to let you stay the night. They probably hope I’m still a virgin!”

“Fine, Leila, fine. I understand,” he said wearily.

After escorting Luca up to his hotel room, my brother and I headed to my parents’ home. I held on tightly to the sides of my seat and breathed deeply.

“Hey, chill out. It’ll be fine,” my brother said, laughing.

“Yeah, sure, try telling your girlfriend that Mom refuses to meet her,” I countered through clenched teeth.

When my brother and I opened the front door of my parents’ home, the mouthwatering smell of cumin and fried onions greeted us.

“Papa? Mummy? We’re home!” I shouted, as I placed my shoes in the hallway closet and walked toward the kitchen. My mother was listening to an Urdu translation of the Qur’an on her cassette player and preparing little balls of minced meat for kebobs. I leaned against the kitchen’s island.

“As-salaam-alaikum, Ma,” I greeted her hesitantly. She had prepared so much food; platters of biryani, raita, naan, and kebobs were lined up on the counter. The table was set, but when I counted the place settings, I felt stung. Why had she made all this food when she had no intention of eating with us? I figured part of it was her pride. She often emphasized our culture of hospitality and serving guests properly. But so much effort to insist on these values? I was at a loss, unable to decipher the full extent of her intentions. “Ma, how are you? The food smells incredible.”

“W

a-alaikum-asalaam,” she answered, keeping her gaze fixed on the crackling frying pan.“Ma, I think Luca would love to meet the person who made all this delicious food,” I said.

“Leila.” She put down the spatula and turned to me. “I never imagined that my grown daughter would bring her gora boyfriend to my house. Never. Every single one of your cousins has married a Pakistani Muslim. Your sister is married to a Pakistani Muslim. Why are you doing this to me? To our family?” The veins in her neck bulged. My face reddened. She was right. Even I had to admit that I had never seen myself bringing a white, Catholic guy home to meet my parents. I sometimes wished that I had found a Muslim man who would help me embrace my roots. But I hadn’t.

“Ma, I’m sorry it didn’t go according to plan, but I have been with this person almost three years now, and it’s serious. You know I tried meeting Muslim men.”

“You mean the ones you met in Tunisia?” she asked derisively.

“Yes, I met someone there. Don’t you remember?”

My mother picked up her spatula and started flipping the kebobs. “I don’t know what I did to end up with a daughter like you. What did I do wrong, other than bringing you to this country?” she muttered, jabbing at the food. A hard lump rose in my throat.

“Ma, all I can say is that Luca has flown from Luxembourg to meet you and Dad.” I shrugged my shoulders and went upstairs.

My mother never met Luca. She went to a friend’s house that evening as the rest of us ate the dinner she prepared. At the beginning of the evening, when Luca learned that my mother would not join us, he became anxious. “What? Why?” His face went ashen; his eyes darted around the room. He looked around the house, peppered with framed pictures of the Kaaba in Mecca and gilded Qur’anic verses, and tasbih beads in every corner.

My father was stiff and awkward around Luca at first. And Luca had trouble understanding my father’s accented English, and kept looking at my brother and me for help. But after Luca helped himself to a third serving of my mother’s biryani, exclaiming repeatedly how much better her cooking was than that of any Indian restaurant he had ever visited, my father beamed and began explaining the differences between Pakistani and Indian culture. I’m not sure how the conversation turned to politics, but suddenly the men at the table were animated, each one impatient to express his viewpoint on how to deal with Al Qaeda, Kashmir, and Iran.

Love, InshAllah

Love, InshAllah