- Home

- Nura Maznavi

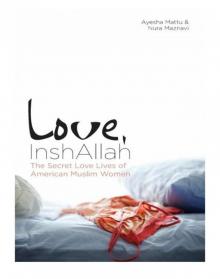

Love, InshAllah Page 19

Love, InshAllah Read online

Page 19

“Okay, is that it?” He was obviously trying to get me to go more deeply into myself, to find the root of the problem, not its many stems. It soon became clear: I wanted to please God.

Once I realized my bottom line, it became easy to wake up for Fajr and refuse non-zabiha meat. Instead of feeling sorry for myself, I felt gratitude for God’s innumerable graces. Ali became my spiritual advisor. He sent me books on the Prophet and the Prophet’s family and encouraged and helped my Arabic and Qur’anic studies. I read everything he sent me, which solidified my beliefs once again. I began to wear the khimar and identified myself with the Shi’a school of thought. Ali’s letters and phone calls came whenever I felt myself slipping back into doubt, and my faith in him grew alongside my faith in God.

We conversed about my son and about my plans to become a midwife; he told me about the communal business he ran with the brothers of his jamah, and their desire to live self-sufficiently. Within the year, talk turned to marriage, both a hopeful prospect and a dreadful thought. Was I ready to do this again? Ali believed that both of my previous marriages had failed because he was my match. God meant for us to be together, he said. Our paths certainly had crossed many times, and we seemed to fit together perfectly, but for one thing––Ali was already married.

Even though I had heard that polygyny always ended in broken hearts, mayhem, and dismemberment, the idea of sharing a husband had never bothered me. I had never understood why women fought so much over men. If a man loved two women, the women could either leave or share him. I believed women should be confident enough in themselves that they wouldn’t need to be the sole object of a man’s affections. I knew there were men who loved and supported two families with equal devotion. To me, husband sharing sounded like the perfect blend of being married and single at the same time. I would have a loving partner to care for me, and time alone to care for myself. In every holy book I’d read, God was clear that love, unlike money, is infinite; it’s a metaphysical commodity that grows when shared. In short, polygyny seemed not an unholy aberration, but a sacrosanct communion between a family and God.

I realized that most other women did not share my philosophy, and I had already decided that I’d never marry a man whose wife did not agree with having a co-wife. Ali said his wife, Hajar, was an exception. He said she was fully aware of our relationship and supported it openly. Learning that eased my worries some, but I still had to hear it from Hajar herself.

Hajar and I had spoken many times before, and so, during our next conversation, I asked her what she felt about the idea of our sharing Ali. I began uncomfortably, unsure of what to say, but Hajar was quick to put me at ease. She told me that she had traveled to Africa when she was younger and lived with a polygynous family. Seeing the community they had together, she knew that she wanted a marriage like theirs. Ali had told her soon after they met that he felt obligated to marry more than one woman; there were too many single women in the ummah for him to care for just one. Hajar agreed, and said she believed that I was the right woman to join their family. She invited me to visit them in San Diego, to see their home, meet the rest of the family, and feel what it would be like for it to be mine, too.

I bought a ticket and scheduled a two-week visit to San Diego.

Ali—nine years my senior, tall, fat, with a beautiful obsidian complexion—picked me up from the airport. Seeing each other in person for the first time ever, we both felt we were greeting someone we had known our whole life. He even claimed that for decades he had dreamed of someone who looked just like me. It sounded like a seriously lame line, but Ali was not one for lines.

I met Hajar and some of the men in the community that night. We prayed Maghrib and Isha in congregation. My room was a cozy sanctuary: olive green walls peppered with framed Qur’anic calligraphy, hadith, and God-focused poems Ali had written. I slept on the floor on a comfortable futon.

The next day, Hajar took me out. We sat alone together and talked. When I looked into her eyes and asked her if she was really willing to share her husband, she told me she was, and I knew she was speaking truthfully. She had married Ali after twenty-five years of being single. She liked being married, but after five years of being the sole spouse, she was ready for a sister wife.

The decision to share was solely mine. I had to decide if this was the right life for Raheem and me. It seemed so. I loved Ali and the feeling of his home; it was very much like the warmth of community I had felt when I first converted, and that I hadn’t found since. I woke up every day to the adhan and the Southern California sun. The extended family prayed in congregation. We ate dinners together each night: salads with homemade dressing, whole-grain bread, fresh vegetables and fish, or zabiha chicken on the weekends.

I had been in San Diego for six days when Ali asked me again to marry him and Hajar asked me to join their family. As perfect as everything seemed, I was afraid to make the decision. I recalled that my engagement to Ishaq had seemed “perfect,” too. I no longer trusted myself to make up my mind. It wasn’t just about me, either—Raheem had never met Ali. Interviews of traumatized stepchildren on Oprah flashed through my mind. I also had no idea if sharing a husband would actually work. Now that it was time to commit to a polygynous life, my faith in its success was greatly shaken. Additionally, I had received a scholarship to attend nursing school in Durham, and classes would begin soon. My return flight to North Carolina was in eight days; I had to resolve this before then. Hoping to clear my heart, I sought out the Knower and Source of all Outcomes to tell me what He wanted for me. I did the only thing I could do: I took out a prayer rug and made istikharah, a special supplication to God to clarify a difficult decision.

Istikharah literally means “to seek goodness from Allah.” The answer sometimes comes in a dream by the end of the seventh day of prayer. For the first four nights after I began to do istikharah, I felt just as frightened and confused as I had before. On the fifth day, I read extra passages from the Qur’an, taking my time. Day six heralded nothing new. I felt lost and worried. God was not going to answer me!

That night, I carefully pronounced each word of the prayer in Arabic and in English. I woke feeling the same. This coming night would be the last. Distressed, I stayed in my room the entire day. I didn’t want to pretend everything was okay when nothing was. This was a pivotal moment in my life, and I didn’t know what to do. I cried for the first time in years, begging Allah to send me a sign. I tossed and turned on my bed, falling asleep two hours later.

And I dreamed.

It was a sunny, cloudless day with deep-blue skies. Ali, Raheem, and I were standing on a hilltop covered with huge white daisies. Ali wore a white prayer robe, Raheem was in a white shalwar kamiz, and I had on a white gown and scarf. My son and I ran playfully down the hill, laughing. Ali gave chase close behind. Just before we all reached the bottom of the hill, Ali grabbed me by the waist with his right arm, and Raheem with his left. He swung us around, holding us tightly to him.

I sat straight up. God’s message was clear: Ali was, literally, the man of my dreams. The next morning I told Ali and Hajar I would absolutely love to join their family.

I returned to North Carolina to wait for my brother’s return from the Gulf War, quit school, and pack. It took five more months to relocate, and Shaytan did his damnedest to get me to renege on my intentions. He murmured his fear of poverty if the family business failed. He whispered that I might regret giving up an educational grant. He mumbled that Raheem was already emotionally bruised and I was putting him at risk for more. He screamed doubt into my heart about the possibility of co-wives’ ever getting along. He conspired with my vanity: Ali was not handsome like Talib, nor as wealthy as Ishaq, and was very overweight. Above all, he tried to make me forget the signed, sealed, and delivered message God had sent me directly.

Ultimately, Shaytan failed. The dream remained as vivid in my mind as the night I’d had it. Ali, my long-distance empath, always called right on time. His voice was all I needed

to reassure me that I was doing what Allah willed.

Raheem and I moved across the country to our new life. At first, I stayed in one of the two houses the jamah rented; Hajar stayed in another. Ali alternated spending three nights with each of us. Our village helped me raise Raheem and the other children born to the jamah. We prayed Fajr, Maghrib, and Isha together every day. The sisters took turns preparing dinner. We all lived off the profits we made from our carpet-cleaning business. There was more time to pursue our own interests. Hajar was able to work full-time, and I became a doula-midwife and homeschooled Raheem. As living arrangements and economics changed, we adapted by working together, relying on Allah to go forward.

We’ve been a family for twenty years now, living together in one house for the past fourteen. Hajar and I are like sisters, and she is Raheem’s “Mama Two.” I’ve felt at home with her and Ali since we first moved in. Muhammad, my surprise “subhanAllah baby,” was born four years later.

The interplay of free will and fate is interesting. Although God does not make mistakes, people often do. I’ve wondered if my former marriages were errors, or what I needed to go through to prepare me for my marriage to Ali. Allah, in His infinite mercy, answered my dua and delivered my soul mate, complete with a Technicolor dream to make sure I got the message, alhamdulillah.

We never expected everything to be perfect, and it never will be. We’ve learned to compromise and be patient with one another as needed, and to cherish the good times, which far outnumber the bad. That’s all it takes for us to be content. For the first time in my life, I feel whole, in myself, in my family, and in my faith.

A Journey of Two Hearts

J. Samia Mair

My parents made a conscious decision to raise me as a boy. Instead of learning how to cook and clean, I mowed the grass and shoveled snow with my father. Every fall Sunday, I sat next to my father on the couch, watching the Pittsburgh Steelers play football. In sixth grade, I could beat every boy in my class in the mile run. I was the son my father never had, and it was a role I embraced.

Surprisingly, my parents had a traditional relationship themselves. My father worked to support the family, and my mother stayed at home. But I grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, and even my parents got caught up in the hippie and feminism movements that swept the country. I can still remember my mother’s silver paper minidress that was far too revealing for her hourglass figure. By wearing it, she told the world that she was a liberated “womon.”

Unlike my mother, I was expected to get a doctoral degree and support myself. Depending upon a man was out of the question. My parents wanted me to be fiercely independent and think for myself.

For the most part, I met their expectations. I graduated with a degree in geology from Smith College, where I was surrounded by high-achieving, goal-oriented women. My father was an attorney, and I decided to follow the same path, even attending his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania Law School. I did well there and eventually ended up working as a prosecutor in the appeals unit of the Philadelphia district attorney’s office. A prosecutor’s office is no place for timid men or women, and I held my own among even the most hardened attorneys.

Although I was a tomboy and raised to be independent, I always wanted to marry my Prince Charming. I dreamed about a handsome man sweeping me off my feet and carrying me away to happily ever after. As I watched my parents’ long-standing, unhappy marriage deteriorate into divorce in my early twenties, I vowed not to let that happen to me. But by the time I was in my early thirties, I was divorcing my second husband.

I met my first husband in college while I was still dating my high school sweetheart. He was a few years older than I was and had been a corpsman in the Navy but stationed with the Marines. His many adventures around the world intrigued me. He made me laugh, and we had a lot of fun together.

But he turned out to have a drug and alcohol problem and lied incessantly. I learned that most of what he had told me about his past was fabricated, including his stories about his adventures in the service. The more the truth came out, the more I realized that I did not know my husband; I felt like I was married to a stranger. I thought that with my love and support he could turn himself around, but, like so many women who feel this way, I was wrong. Even after he went to rehab to address his addiction, he could not stop lying, and eventually I realized that I did not want to spend the rest of my life with someone whom I could not trust. We separated during my second year of law school, after only a few years of marriage.

Four or so years later, after a few relationships in between, I met my second husband. Although we did not know each other long, I felt that I had finally met my soul mate. He worked for a nonprofit organization, building homes for the poor. He seemed to be civically minded and treated me well. At the time, I was working at a stuffy, corporate law firm and was very unhappy in my work. He would often pick me up at my office on his bicycle and ride me the thirty minutes home on his handlebars. When I quit my job and moved to Brazil for six months to work on indigenous rights, we continued dating. We decided to get married when I returned.

I felt so lucky to have found him. But once again, I ignored the red flags that should have scared me away. He was not nice to his mother and had difficulties with some of his colleagues at work. As soon as we returned home from our honeymoon, he changed. He stopped helping around the house, telling me he was no longer going to cook or clean. He tried to monitor my every move and undermined everything I did. He constantly accused me of being unfaithful. When he got mad at me—which was often—he would not speak to me for weeks. When he started throwing things at me, my friends told me to leave him. He had all the signs of an abusive husband—he just hadn’t hit me yet.

Later, he told me that he used the book The Art of War to guide our marriage. He wanted to deprive me of everything and then slowly give me back some of my “privileges.” We went to counseling, and I spoke to the priest who had married us. You know that your marriage is in trouble when your priest advises you to divorce your husband. I took the advice and moved out, embarrassed and ashamed to be in my early thirties and getting divorced a second time. My priest also told me that I needed to choose a different type of man. I started thinking about my choices and realized that “bad boys” attracted me. I used to like a bit of bravado, bordering on obnoxious. Looking back now, I cannot understand the appeal, but it was there.

Nine months later, I was ready to date again. I was now working in the district attorney’s office, and a colleague there suggested that I meet his friend Mike, who was a molecular biologist and, by the way, also modeled. To entice me, my friend showed me Mike’s comp card, a collection of photographs on eight-by-eleven-inch card stock that modeling agencies put in display racks for potential clients. Intelligent and gorgeous? I was interested.

We met at a bar for our first date and played pool most of the evening. That date led to others, and I soon discovered that, in addition to being good-looking and smart, Mike was kind and funny and loved children. He also was an excellent cook, which was a huge bonus, since I hated to cook. My dinners usually consisted of cold tofu, cut right from the package, and Grape-Nuts cereal.

Not long after we started dating, I realized that Mike thought I was several years younger than I was (I was five and a half years older than him) and that I had been married only once before. I had told my colleague who set us up to tell Mike my age and my divorce status so that he would know my situation up front. But clearly, my colleague had gotten it wrong.

I agonized over what to do. I really liked Mike and did not want to scare him away with the truth. If someone wanted to set me up with a man who had been married twice before, it would give me pause. I could understand his hesitation. All of the women whom I asked for advice told me not to say anything until he got to know me better; presumably, my “winning personality” would eventually overshadow my inglorious past. The one man I asked told me I should say something immediately; otherwise, it would be disho

nest, which, he noted, isn’t a very good way to begin any relationship. I took his advice and carefully raised the subject with Mike.

“How old do you think I am?” I asked.

“Thirty-one or thirty-two,” he replied.

“I’m actually thirty-four.”

“That doesn’t bother me. I once dated someone eight years older than me.”

I continued, “How many times do you think I have been married?”

“Once?”

Okay, here goes, I thought to myself. “It’s actually twice.”

There was a slight pause before he answered, “Well, my stepfather was married twice before he married my mother, and he’s a great guy.”

A longer pause ensued; then he asked, “Do you have any children?”

Luckily, the answer was no. If I had had kids, I believe it would have been a deal breaker.

After we had been dating a little over a year, I moved to Baltimore to get a master’s in public health from Johns Hopkins. I was disillusioned with the criminal justice system and wanted to learn how to prevent violence. Mike moved in with me about a year later, and we started to plan our life together.

Part of that planning involved discussions about our spiritual beliefs. At the time, I would say, I was spiritual but not religious. Both of my parents were raised Catholic, and I was baptized as a Catholic. Despite my father’s upbringing, he was and still is a devout atheist. He taught me that God did not exist and only fools followed a religion. There was no afterlife, and the stories in the Bible were bizarre fairy tales—a crutch for the weak. My mother took my sister and me to a variety of churches off and on when we were young, but by the time I was ten, we stopped going altogether. I cannot recall God or religion ever having been mentioned in our house in a positive manner. Even as a young child being raised as an atheist, though, I always believed that there was something more.

Love, InshAllah

Love, InshAllah